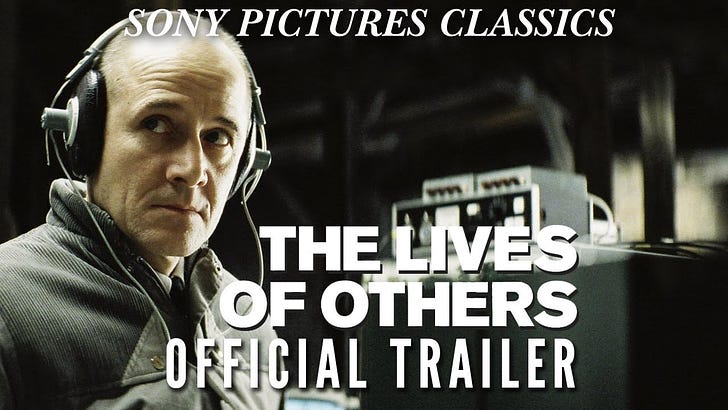

There’s a moment in The Lives of Others—that haunting German film about surveillance under the Stasi—when the interrogator doesn’t raise his voice. He doesn’t slam the table. He just waits. That’s the test. Not whether the subject breaks, but when. Not whether they’ll speak the truth, but how long they can delay the betrayal of it.

That’s the new shape of authoritarianism: soft, procedural, ambient. And if it feels familiar lately, it’s because we’ve spent decades rehearsing it on screen.

Authoritarianism has always been the villain of fiction. But now it’s slipped the frame.

We’re not just watching the dystopia. We’re in it.

And the twist isn’t that no one saw it coming.

It’s that we saw it so clearly, and still let it in.

“He who controls the past…” —George Orwell

In fiction, the autocrat’s weapon is always the same: control of narrative.

In 1984, it’s the revision of history.

In The Handmaid’s Tale, it’s scripture weaponized.

In Fahrenheit 451, it’s the erasure of books—and with them, memory.

The totalitarian impulse doesn’t begin with tanks in the streets. It begins with what cannot be said. With the syllabus altered. The book removed. The teacher warned.

We’re watching this happen in real time, only now it comes wrapped in the language of “parental rights” and “curriculum transparency.” In Florida, entire libraries are being boxed up under the guise of review. In Texas, a teacher was fired for assigning Between the World and Me. In Tennessee, a school board banned Maus—not because of the Holocaust, but because it depicted nudity in cartoon mice.

The modern loyalty test isn’t shouted—it’s quietly administered.

A question. A hesitation. A consequence.

The Aesthetic of Obedience

Cinema has always been obsessed with fascism’s look. The polished boots. The uniforms. The choreographed marches. The Conformist (1970), perhaps the most visually elegant film ever made about fascism, shows us the real danger isn’t ideological. It’s aesthetic.

Fascism, in Bertolucci’s world, is less about Hitler than it is about style. About a man so desperate to fit in that he hands over his conscience in exchange for symmetry.

That’s what makes modern authoritarianism so potent: it doesn’t feel like tyranny. It feels like order. Like competence. Like cleanliness.

We see this too in Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, where fascism arrives not with a gunshot but with an awkwardly polite request for papers. The concierge resists not through violence, but through small, cumulative acts of refusal. Civility becomes subversion.

Network and the Monetization of Outrage

If The Conformist is about the aesthetics of fascism, Network is about its soundtrack.

Rage. Performance. Spectacle.

Howard Beale’s legendary on-air breakdown—“I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!”—wasn’t a rebellion. It was a ratings strategy.

That’s the loyalty test in America now. Not will you obey, but will you perform outrage on cue?

The media-industrial complex, right and left, has learned to monetize indignation. Autocracy no longer needs to silence dissent. It simply commodifies it, rendering it impotent through repetition.

And the audience? We become complicit. We watch. We share.

We get mad—but we keep scrolling.

Children of Men and the Collapse of Possibility

One of the bleakest dystopias in film is Children of Men. Not because it’s violent, but because it’s quiet.

The world ends not with a bang—but a bureaucratic whimper.

Borders close. Rights recede. Hope becomes nostalgia.

In that film, the great horror isn’t dictatorship. It’s exhaustion. The populace isn’t terrorized—they’re numb. The loyalty test, in this future, isn’t who you support. It’s whether you still believe in anything at all.

Sound familiar?

The Truman Show and the Architecture of Illusion

We like to think we’d know if something was wrong.

That we’d see the walls of the set.

That we’d realize the news was scripted. That the story we’re being sold was fiction.

But like Truman, we often don’t know we’re trapped until we try to leave.

The algorithm is a narrative. The feed is a plot engine. It tests us not for our loyalty to a regime, but our willingness to remain distracted. We’re not surveilled—we’re programmed to perform surveillance on ourselves.

And when we finally push against the edges, we find Ed Harris in the control room, softly reminding us: “There’s nothing out there for you.”

Jazz, Resistance, and the Loop That Breaks

But here’s the thing.

Every dystopia eventually hits a dissonant note. A moment that refuses to resolve.

In V for Vendetta, it’s a masked figure reading banned poetry.

In Fahrenheit 451, it’s the memory walkers reciting books aloud in the woods.

In Children of Men, it’s a crying baby that stops a war.

Resistance never looks like revolution at first.

It looks like noise.

Like jazz.

Thelonious Monk once said: “The piano ain’t got no wrong notes.”

That’s how you break a loop. You play a note the system didn’t expect.

That’s how stories survive. And why regimes always try to erase them.

Final Credits

We’ve seen this plot before.

We wrote it. We filmed it. We studied it in English class.

The question is whether we’ll recognize the loyalty test—not when it comes from the state, but when it arrives in the form of comfort.

It doesn’t ask you to betray your beliefs.

It just asks you to keep scrolling.

To stay quiet.

To look away.

The test has already started.

Watch, Read, Reflect

Fiction & Memoir

1984 – George Orwell

The original loyalty test. Still chilling. Still relevant.The Handmaid’s Tale – Margaret Atwood

A parable of theocracy and surveillance—and how scripture becomes strategy.Fahrenheit 451 – Ray Bradbury

On erasure, media saturation, and the slow death of curiosity.The Plot Against America – Philip Roth

A counterfactual history that feels less fictional by the year.Between the World and Me – Ta-Nehisi Coates

A real-life loyalty test—in the form of a father’s letter to his son.On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century – Timothy Snyder

A slim, powerful field guide for resisting modern authoritarianism.The Fire Next Time – James Baldwin

Not just a warning. A reckoning.

Films & Series

The Lives of Others (2006)

The quiet mechanics of surveillance—what it takes to watch, and what it costs to stop.The Conformist (1970)

The most beautiful film about cowardice ever made.Network (1976)

The origin of infotainment—and the rage machine we never turned off.Children of Men (2006)

Dystopia by erosion: the future drained of possibility.V for Vendetta (2005)

A comic-book parable of resistance, poetry, and masks.The Truman Show (1998)

When the algorithm is the architect—and your life is the content.Good Night, and Good Luck (2005)

Murrow vs. McCarthy—and the burden of telling the truth on television.The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

Fascism in pastels—where resistance is civility, and courtesy becomes rebellion.

Nonfiction & Criticism

Amusing Ourselves to Death – Neil Postman

How the medium became the message—and the distraction.The Age of Surveillance Capitalism – Shoshana Zuboff

Your behavior is the product. Welcome to the new panopticon.Propaganda – Edward Bernays

The 1928 playbook for manufacturing consent. Still in print, still in use.We Have Been Harmonized – Kai Strittmatter

On China’s digital authoritarianism—and what it predicts for us.How Fascism Works – Jason Stanley

The vocabulary of authoritarianism, decoded.

Stories have always been the first thing autocrats try to control—because they know something we often forget:

Narrative shapes memory. Memory shapes identity. And identity shapes resistance.

The books and films on this list aren’t just cultural artifacts. They’re warnings. Rehearsals. Sometimes even blueprints. Not of how to build a regime—but of how to recognize one before it finishes building itself.

If you’re reading this far, you’ve already passed the first test:

You’re paying attention.

Keep reading. Keep watching. Keep telling the truth, even when it’s easier to let the scroll do it for you.

Because the feed may be endless—but so is the story we write to resist it.

That’s it for this week. Stay cool!