Coming Thursday: A new short story from the world I’ve been building quietly for years.

This one’s free. Future stories like it may not be.

The story is called The Village That Forgot the Moon.

A child hears a song no one else remembers. A well begins to hum. And something buried in the ash starts to stir.

It’s not a prequel or a chapter—just a standalone myth from the edges of my upcoming novel. A whisper of the world to come.

Watch your inbox Thursday morning.

Note: You may have noticed that New Fiction Press now has a paywall. Don’t worry—if you’re a free subscriber, the Sunday essays you’ve come to expect are still yours, no charge. Paid subscribers just get a little more: full stories, bonus fiction, behind-the-scenes content, and early access to what’s next.

Now, on with the show.

—————————————————————————————————————-

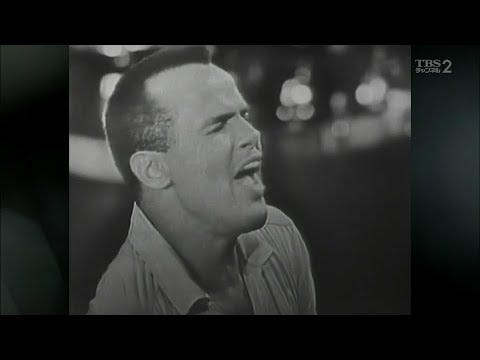

60 Minutes with Harry Belafonte

Somewhere out there—in the multiverse or maybe just my imagination—there’s a version of me who walks into that Manhattan suite with Harry Belafonte and walks out with a deal. A handshake. A green light. A yes.

Call it Earth-44. A place where memoirists get development deals over breakfast, civil rights legends don’t age, and the past is always open to revision. That version of me is confident, composed, maybe even clever enough to win over a man who helped orchestrate history.

But that’s not this universe. Not the one we’re scrolling through now.

In Everything Everywhere All at Once, Evelyn Wang slips through lives she never lived. She’s fractured and infinite—mother, fighter, chef, lover, singer, disappointment, dream. She’s haunted by the idea that somewhere out there, she could’ve been more. Or maybe just different. The film isn’t about timelines so much as it is about regret. Choice. Chaos. And the unbearable weight of being alive right now.

I think about that movie a lot. Not for the googly eyes or the kung fu. But for what it says about fragmentation. About possibility. About how hard it is to hold the thread.

Then I remember Belafonte. And the way he made one life feel like a thousand.

The Manhattan suite was a study in quiet elegance. Muted greys and creams softened the room, casting calm over the chaos of the city outside. It was early 2000s New York, and I had been sent by A&E to pitch a Biography episode. The assignment carried a thrill, but I felt the weight. This wasn’t just another celebrity profile. This was Harry Belafonte—a man whose name conjured artistry, activism, and a moral clarity that belonged to another era.

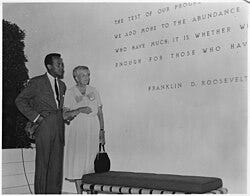

I’d met icons before. I’d interviewed Muhammad Ali, who turned conversation into sparring. I’d spoken with James Baldwin, whose words cut like a scalpel. I’d stood near the balcony of the Lorraine Motel, the sacred ground where Martin Luther King Jr. took his final breath. But as I waited for Belafonte, I felt a different kind of anticipation—a sense that I was about to meet someone who hadn’t just witnessed history but had shaped it.

When he entered the room, his presence was immediate. He moved slowly, deliberately—frail in motion, stout in presence. Like a tree weathered by time but still rooted deep. His handshake was firm, his eyes sharp and measuring—not just my words, but what stood behind them.

“Sit,” he said, his voice low and resonant, like a bassline in a jazz composition. “Let’s talk.”

And talk we did.

From the moment he spoke, it was clear I wasn’t just conversing with a man—I was engaging with a living archive. This was a man whose stories wove through time: from “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)” and Carmen Jones, to marching with Dr. King and strategizing with Malcolm X.

He had been a star when the world first saw him. But fame wasn’t the goal. It was the lever. He used it to lift movements, fund marches, call power to account. “The stage was never just for applause,” he said, leaning forward. “It was a pulpit, a battleground—a way to make people feel something bigger than themselves.”

That line stuck with me.

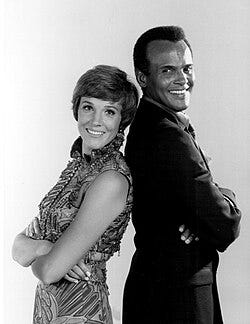

There was no split in him between entertainer and activist. The records, the roles, the rallies—they were all the same act of resistance. He spoke during interviews of the degrading scripts he turned down, the TV stations that threatened to censor him, the collaborations he defended when Southern affiliates refused to air shows with integrated casts. He held the line. “They think they’re doing you a favor,” he said. “But dignity is not a favor. It’s a right.”

He didn’t speak to me with fire or anger. He spoke with clarity—the kind that comes from years of choosing your battles and knowing exactly why.

As I listened, I couldn’t help but reflect on my own work—the compromises, the quiet calculations, the ambitions I’d reshaped to fit someone else’s expectations. Belafonte’s stories didn’t just recount a life. They demanded I examine mine.

When the time came, I delivered my pitch—respectfully, earnestly, knowing full well I was treading sacred ground. He listened. Thoughtfully. And when I finished, he said what he had to say.

“It’s a good idea. But it’s not for me.”

No anger. No ego. Just a line drawn.

And just like that, he reminded me: not all stories are for sale. Not all timelines converge.

Back in Everything Everywhere, Evelyn Wang is spinning—through what-ifs, what-might-have-beens, the infinite scroll of unlived lives. But Belafonte? He chose his. Not because they were easy—but because they mattered.

He didn’t want a memoir. He was one.

He didn’t need a cable TV documentary. He lived in the uncut footage.

And maybe that’s the contradiction I keep circling: in a world that wants everything, everywhere, all at once—the most radical act is to hold the line. To say no. To protect your signal from the noise.

Now, here we are—living inside Evelyn’s everything bagel. Every breath a brand. Every scroll a scream. The feed spins fast, the rent comes due, and stories get flattened into content.

But Belafonte knew what most of us forget: refusal is a form of power.

So no, I didn’t get the project.

What I got was better.

I got clarity.

Belafonte showed me that in a world chasing infinite versions of self, dignity is the one thread that doesn’t glitch.

And somewhere—maybe not Earth-44, but somewhere—Evelyn Wang would understand.

The most radical act isn’t flight.

It’s refusal.

Harry Belafonte’s story was never mine to tell, and that, I think, was the point. In refusing to let me borrow it, he ensured that it remained true, untarnished, and wholly his own. And in doing so, he gave me a story I never expected—the story of a man whose greatest act of defiance was living life entirely on his terms.

In every timeline, dignity sounds the same. And in this one, it was a bassline in Belafonte’s voice, humming long after I left the room.