The city in my dream is never named. But I know it like I know my own breath.

Always night. Not velvet, not romantic—just dark. Power outage dark. The kind of night that feels planned. The buildings lean in. The air is wet with warning. Somewhere behind me—footsteps. Threats without faces. Men, maybe. Or memory.

I run. I always run.

And then: I rise.

Like a cut to wide shot in a film. My body lifts. The ground drops. I’m above it all—alleys, streetlights, sirens fading into nothing but grid. That’s the moment. That breath. It feels like deliverance.

But it never lasts.

The air thickens. My arms forget what they’re supposed to do. I begin to fall—not like a scream, but like a slow unraveling. A reminder.

The dream always ends the same: just before the crash.

But I still wake up sore.

I used to think it was just stress—that dream. But it’s not about running, not really. It’s not even about flying.

It’s about the moment after.

The inevitability.

The crash.

Icarus tried to rise, too. Wings made of wax and warning. Told not to fly too high, not too low. Stay in the safe middle. But flight—real flight—never stays safe. And for those of us born into systems that were never built to hold us, every ascent is a defiance.

That’s why the fall stings. Not because we flew too close to the sun.

But because we believed we could.

I think of Nope—Jordan Peele’s slow-burn vision of survival under spectacle. A Black horse trainer. A watchful sky. An alien that feeds on attention.

They learn the hard way:

Don't look up. Don't look back.

Looking can cost you everything.

It’s a film about flight—but not the kind we dream about. The kind you try to avoid. The kind where freedom means breaking line of sight, not breaking through.

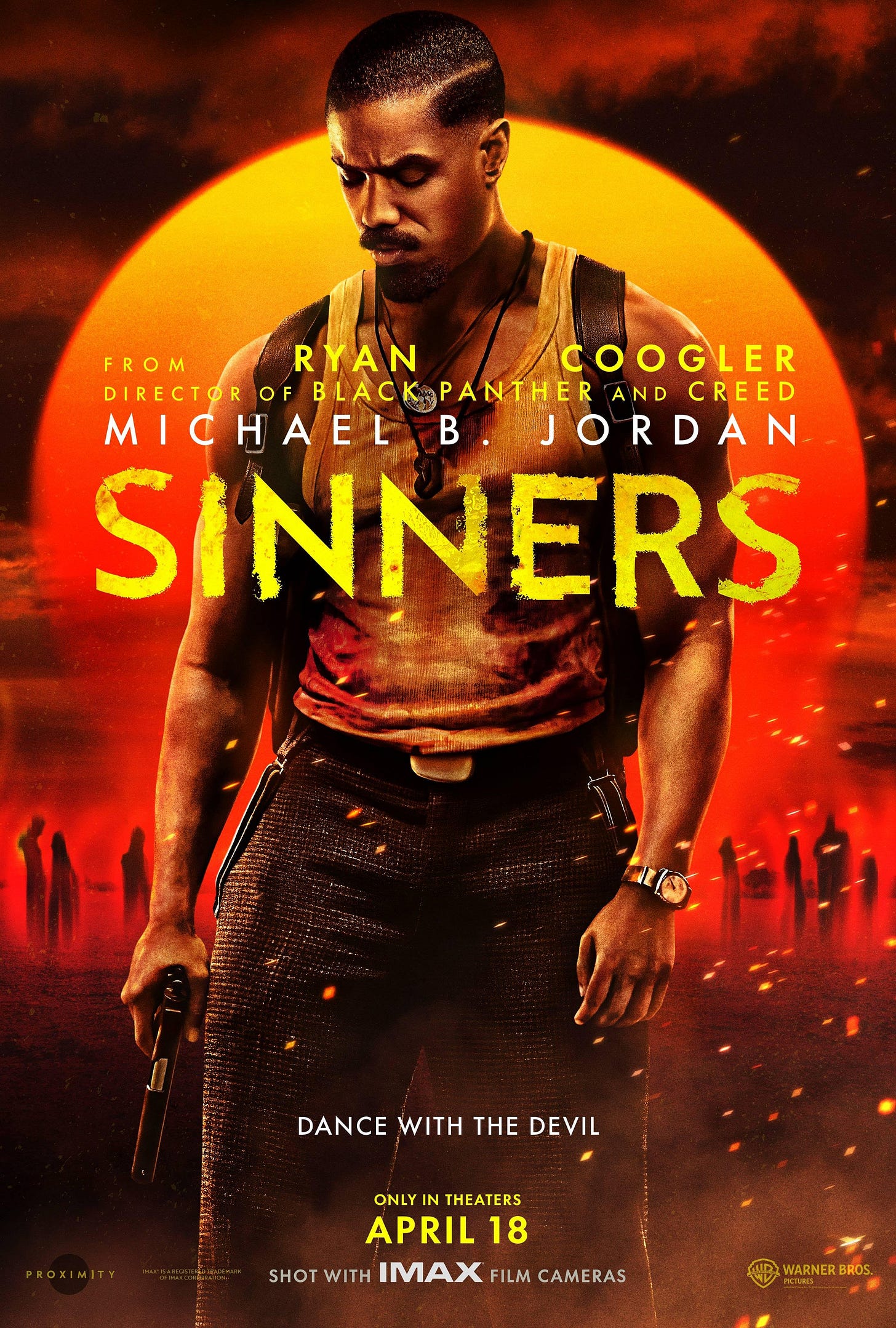

In Ryan Coogler’s new inspiring film, Sinners, twin brothers take flight—not with wings, but with music, memory, and a dream of building something sacred in a land that treats their very breath like trespass. Smoke and Stack return to the Mississippi Delta to open a juke joint, a sanctuary of sound in a haunted world. But what they find waiting isn’t just Jim Crow or the weight of the South—it’s something older, hungrier. A white vampire wrapped in charm and bloodstained linen. Flight in Sinners is never literal, but it’s always urgent. These brothers move not to escape, but to reclaim—to take back rhythm, land, history. And like every flight I’ve ever taken in a dream, theirs is shadowed by the question: how long before the fall?

Then there’s Harriet. Tubman, of course.

She flew without wings. Led others by starlight and silence. Slipped through nightscapes like smoke. If the crash came for her, it never caught her. She flew knowing the danger. Flew anyway.

They say she never lost a passenger. Maybe because she didn’t fly for escape. She flew for arrival.

The dream I keep having—it’s not just mine. It’s stitched into our stories. Black flight has always been a risk. Always a performance. Always a question of how long the air will hold us.

Whether it’s Milkman flying off that cliff or Kendrick saying, “We gon’ be alright” while the ground trembles beneath him, the message is the same:

Freedom is never given.

And gravity is political.

These days, the dream comes less often. But the rhythm? Still here.

Scroll long enough and you start to feel lifted. Viral. Seen. You hover for a moment above the noise. But that’s not flight. That’s bait. The feed isn’t wind—it’s wire.

And every platform has a gravity setting. Every scroll ends in a crash.

So I keep asking:

What if the dream could change?

What if one night, I stopped running?

What if I turned around and faced what was chasing me?

What if I flew not to escape, but to return?

Not to vanish, but to arrive?

What if the dream wasn’t about the crash at all—

but about who still gets up afterward?

A fascinating dream and a fascinating metaphor!